or years I crossed Campos Gerais, constantly traveling between Northern and Eastern Paraná, viewing – nearly always through sunshot windows dulled by cold – its ice-cold rivers on their stony beds coursing through meadows, here and there the concentrated dark green foliage of araucarian groves around a stream; farther away, rocky outcrops evoked ruined structures; the harsh jut of escarpments; filled with the sound of the underground rivers, waterfalls and sinkholes which have obeyed and shaped this place for millions of years, this Brazilian landscape upon which my ancestors were born and lived for more than ten generations.

At first sight, On the glittering screen of the eyelids arose out of my desire to plunge into that fascinating landscape and rub off the patina of the dense clouds I’d laid over the land and the image of my family. But my deepest intuition tells me that the germ of the idea was an impulse to see other times within my time, (an)other meaning(s) to my meanings, like the traces of a face seen in the shards of a mirror broken into a thousand pieces. Furthermore, my thinking, moved by a kind of “imagetic concretion”, seeks the abstracted state of conscious daydream or traveling thought, which I entered while reading as a child, lying in a hammock in the shade of sibipiruna trees, pulling together in a sinuous motion like filings to a magnet the diverse reflections in my mind through observation of reality, a state akin to what Fernando Pessoa may have meant when he wrote “what feels in me is thinking”.

It was, then, almost natural for me to imagine a journey through these changing topographies, through this place which in dreams appeared to me as an untranslatable palimpsest – which, its layers rubbed away, revealed now deserts, now seas, brutally blooming flows of lava, valleys, pitch dark deeps, stone molds and a magmatic forge. An infinite palimpsest, always with stubborn signs, one after another, unwilling to be scoured away on its surface, the way we might obstinately refuse to allow ourselves to be given a new, or another meaning. Never a blank page, never a deserted margin where tracks are erased by the sea (which never ceases to await other marks).

Thus, I conceived On the glittering screen of the eyelids as an itinerary, lost somewhere between the archaic and the modern, through this natural and cultural soil which helped to form my vision of the world. I am attentive to diversities, dislocations, cultural exchanges. Because I thought of the project has having a character at once personal and universal, I invited artists and researches to follow the trails with me. Some of them are members of my immediate and extended family. We formed a team of collaborators all of whom share a feeling of being rooted in the place, and whose work has been inspired by it. (See Collaborators: On the glittering screen of the eyelids).

When I imagined this “voyage”, I didn’t know what it held in store for me. Photograms whirled through my head: Guimarães Rosa’s metaphysical sertão, the existential distances of the Borgesian pampas, the fabulous mountains and Andean rivers of José María Arguedas (not to mention Roa Bastos’s hollow trees and burning canoes descending the nocturnal currents of the Chaco), photograms permeated with the same feeling of a peregrine gaze, “a stranger in her own land”, that I felt when I began my incursion into the Mbyá-Guarani universe for my book Roça barroca.

Finally, I disappeared with my collaborators into Campos Gerais, in search of its horizons, its imposing plateaus cut by canyons and rock formations, its mixed ombrophilous forests which are remnants of one of the oldest ecosystems on the planet, with origins in the Triassic and its apogee in the times of the Continent Gondwana). Bit by bit, the texts appeared, and the photographs, drawings and visual palimpsests which together here combine into a kind of symbolic reading of the region (see the Map of Campos Gerais do Paraná, made especially for the project by the geographer Guilherme Vianna Baptista).

During the expeditions with my collaborators, at times I shut my eyes and tried to imagine, as in a dizzying film – composed of different times, simultaneous only in my mind –, scenes of the dramatic geological events that birthed Campos Gerais in its current state. In a chaos of fairytale photograms, I saw the Earth rend itself again, and spurt forth cornucopias of lava through profound fissures; I saw dikes of igneous rock, sudden escarpments, the signature of glaciers in striations dug into stone, the sea finding its atlantic vocation, the fossils of a world once littoral, or delta, or shallow sea; a landscape engulfed. I projected my film on the screen of my lowered eyelids.

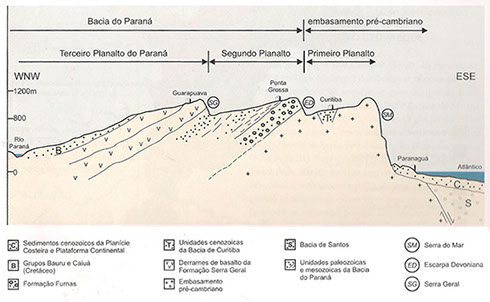

The Campos Gerais we know today is the result of colossal geological transformations in the Paraná Basin – which already existed on Gondwana, long before the formation of South America (see Illustration 1).

The region is testimony to continental drift, the separation of Africa and the South American continent, an event which caused the greatest period of vulcanism ever recorded on the planet. This volcanic period lasted for millions of years and eventually formed the Serra Geral – the western border of Campos Gerais (see SG in Illustration 2).

Viewed as a whole, the geological structure of the Paraná relief is a record of the existence of an ancient Gondwanic plateau which was eroded and sedimented from Serra do Mar in the east, to the bed of the Paraná River, in the west (see Illustration 2); the process resulted in geological and geomorphological features, today recognized as a heritage with world-wide relevance.

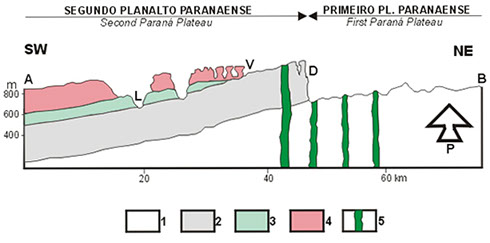

The stratigraphic cut shown in Illustration 2 schematically displays the “plunge” of sedimentary layers from west to east, caused by the formation of one of the largest sedimentary basins on the planet. This has left its mark on the landscape: the structure famously known as Ponta Grossa Arch exposes the outcrop of the Devonian Escarpment (see Illustration 3, which shows the “crown” of the Arch at the eastern part of the Escarpment). The elevation of the eastern crust of Paraná forces the flow of rivers toward the Paraná River, in the interior.

It was here that our work began. We completed one cycle of our project, wandering through parts of the Escarpment, the Guartelá and Vila Velha State Parks –, Vila Velha, with its amazing formations of eroded sandstone (see V in Illustration 3). We saw the canyon and the great rivers (see Collaborators at the Devonian Escarpment). All the while that our work evolved, we were confronted by a reality that none of us had foreseen. This reality was summed up by my son, Pedro Jerônimo, the young photographer on the expeditions, when he said: the countryside looks more like a vast plantation of soy and wheat. Many of the features of the countryside that we imagined we’d encounter were not in sight.

Afterwards, in the winter of 2015, I decided to widen the scope and seek landscapes and images fundamental to the broader outlook of the project. With Pedro Jerônimo as photographic documentarian and his father, the artist Francisco Faria (who contributed the Introduction to The tree of the ridge, a portfolio of Pedro’s photographs), we went to explore the Pines on Serra Geral, still existent in the São Joaquim National Park, in Santa Catarina. Technically, the Santa Catarina Campos de Lages are a continuation of the great geological structure which some geographers call “Peripheral Depression of the Eastern Border of the Paraná Basin”, at altitudes equivalent to those of the Campos Gerais. This explains why the appearance of Campos Gerais do Paraná can be found in that other region: some of Pedro Jerônimo’s photographs of the region in Santa Catarina record the original environment of pre-development Campos Gerais with their imposing pine forests.

Our Journey to the Santa Catarina countryside was made, in part, and with a guide, on horseback, as there are no roads. To reach the abysses of Laranjeiras Canyon, we rode for hours, overcoming stony ravines and quagmires – the horses chose the best way through the mud that almost covered their knees, only stopping to drink water at the arroyos that crossed the trails. We also crossed the National Park, now in a car, along a steep and narrow road with various noteworthy observation points.

After our dérive in Santa Catarina, we decided to go back to Campos Gerais do Paraná and travel an area out of the scope of the first expedition. During a particularly sunny week in the winter of 2016, accompanied by Pedro Jerônimo and the archaeologist Thomas Gaissler, I went to Campos Gerais National Park, looking for araucarian forests and the high fields which gave a name, and fame, to that biome. First, we revisited Vila Velha State Park, with its magnificent sandstone formations that from a distance remind me of the ruins of a citadel. Afterwards, we traveled through a large part of the National Park, walking its environs, until we came to the Tamanduá Historical Fields region.

The photographic record of our most recent travels can be seen in the section entitled The tree of the ridge, which shows everything from preserved dens – like the impressive sinkhole once used by Jesuits as a place for meditation, which gave it its name, Buraco do Padre [Priest’s Hole] – to areas where the Fields and groves provided us with spectacular glimpses of what the area used to look like (examples, not very extensive, of the typical landscape of that phytogeographic region). We passed through woodlands and along slopes where tangled forest is broken by stands of foreign trees like eucalyptus and pine, and everything is cut by sections of Bleak land stripped by the sawmills, Inflorescences, rock formations, and some still-preserved peaks and high plains on the Devonian Escarpment. In “Records of a psychogeography”, his Foreword to Pedro’s portfolio, Francisco Faria speaks at greater length about the transformations which have changed the region’s landscape, particularly since the middle of the 20 th century.

In the time we spent there, we walked narrow asphalt roads and barely-passable trails, foot-worn paths and ways hacked open by machetes; often we did not know where they would end. At times, they ended nowhere: at locked gates, abrupt hillsides or barbed wire. I began to think of that landscape as a clumsily-skinned body; some places were intact, and, in other places, living muscle was exposed. It seemed like a body covered by a shredded cloak.

When I was in my teens I returned to the interior of Paraná, to Curitiba, where I was born, to further my studies; hence the constant comings and goings between the Campos Gerais region and Northern Paraná – whose “red earth”, among the most fertile on the planet, is a soil derived from the magmatism which formed Serra Geral. The Tibagi River, with its source in Campos Gerais, and its mouth on the left bank of the Paranapanema River at the border between Paraná and São Paulo, was my constant companion on that itinerary from the East to the North of the State. Even now, the muddy waters of the Tibagi remind me of the color of the torrents from my childhood.

Speaking of rivers and itineraries, when I was a girl, I loved “inventing” and “publishing/editing” even the most banal event, and a lonely ant balancing on a dry flame tree pod, for example, sailing after a storm in the torrential flood that overflowed the curb and carried in its vortex clumps of red clay, speechless dry twigs and the shock of shipwrecked flowers, them that turn and half emerge and submerge gyring in eddies, these were for me one whole event, which I transformed into a cinematographic epic made up of takes both real and imaginary, and then — foreseeing the murmur of inaudible rivers, still without the knowledge that I lived above the world's second-largest source of underground fresh water, the Guarani Aquifer —, I sat mulling over those things, once beneath blood-colored earth, which, with the heavy rains, had become primeval clay. This poem, for example, suggests a detail, between rojo and violet, of that picture:

hard rain

on banks,

in clods’

reds, over

pebbles

and moss

of the river’s vein

expelled

(knife-edge mire

covers over

cold viscum —

mass of pebbles)

rains in the

muddy bottom,

replete with pigments

drops pull

to surface

in diluted reds

hard rain

(like yesterday)

in the river’s

dark flow (…)

Floating flame tree seeds inspired another poem, with its image of long shadows which only occur in the high, wide plains of Campos Gerais:

limp bell-flowers

waver in the ruins:

first rain

after distinct

shadows

of long suns

curled petals

quake between

black of twigs

wind flails

and pods blast

into seeds

(little ships

casting off from pasture

with their black

scatter of bud

and scrap)

— stones of autumn,

summer’s remains —

relics

However, my little vegetal ships never set sail for the unknown ocean, but for the rivers of the sertão — mythic rivers, so much history flowing together in their courses, rivers over which trees bowed down in specular reverencies, creating changeable reflections for my gaze; rivers running over basalt beds, over dense ironstone spilth (a Gondwanic legacy, I now know); the creeks with their waters tinted different hues from red ocher to the color of dried blood, achiote, blackberry, especially those of the omnipresent Tibagi. Thus that turning, here, from East to North: the pigments and the rapids, whether under the sun there, or under the sun here, slide through my mind in an undivided flow.

Beach of barbaric shores awaiting a body to reveal it, a body wherein it may see itself, under a nebulous blood-red veil is where I situate On the glittering screen of the eyelids. The title of the project, which also reflects the continuity of my poetic itinerary, already suggest that its profound referent is the very “gaze”, and the means by which the gaze – in dream, in the fiction of history, or under the noonday sun – destroys, creates and sees meaning(s). In the project, poetic prospection opens to an intersection of the real, memory and myth, present in the magnificent poem by Jose Kozer, Bestowal; my poem Fable is in conversation with Kozer’s. In this project, I continue seeking hybrid dialogues: see Pedro Jerônimo’s aforementioned photographic portfolio, The tree of the ridge; Vila Velha, Guartelá, a travel journal with drawings by Guilherme Zamoner; and and Nothing is image, nothing is mirage, Maria Baptista’s visual record of passage through Campos Gerais, in which I collaborate with excerpts from poems and books, not to mention my dialogue of more than a decade with Chris Daniels; we have worked together in dialogue in a traductory recreation of this baroque hybrid, the Americas, and the project has gained from his ongoing contribution. Always with history – speech and tale – in the background. The Brief historical and geographical glossary of Campos Gerais do Paraná, researched and written especially for the project by Vera Regina Biscaia Vianna Baptista, defines important historical events, concepts and places related to the region, such as Tropeirismo, Indigenous populations, Quilombos, Immigrant colonies, Jesuit “reductions”, among others specifically related to the region’s geomorphology. A distant breath carried by the wind, a cloud of Amerindian poetry rains on the countryside and mixes with the imaginary waters (eras) of these glittering screens with a poem by Lionel Lienlaf (Alepue, Chile, 1969), in my translation into Portuguese (“O rio do céu"), Chris Daniels’ translation into English (“The river of the sky”), and the original Mapudungun. Literally “the speech of the earth”, Mapudungun is the language of the Mapuche, who live in parts of Chile and Argentina. Leonel, a musician and researcher into Mapuche oral poetry, is a defender of his people’s culture and traditional territories, and his work reflects the living cultivation of ancestrality.

I have one lens trained on the past and another on the present. I go and I come and I remake over and over ways already walked, I follow and pursue buried traditions, the sign of dislocations (as in the metaphor of the marble and the myrtle, in which the marble statue remains always the same, immutable, and the statue carved in myrtle is always bursting forth in lively agitation its anarchic boughs).

In love with geography, the Russian poet Joseph Brodsky probably inherited his interest in travels and dislocations from his father, who was a geographer. Similarly motivated – my family has ties to the overwhelming geography of Campos Gerais (especially the side of my father, Milton Vianna Baptista) –, I noticed something peculiar everywhere we stopped for a time: the rivers running through the place, even those with sources close to the sea, unusually, run inversely, for their courses lead them away from the sea, to stretch out into the interior of the continent – like the nomads Brodsky mentions in an essay, always dislocating toward twilight. In that wandering between sunset and sunrise, I recall, here, the mornings of travel at the beginning of our time spent in Campos Gerais. Frost on the grass. A little fish at the surface of the water. A sheet of water on stone slabs. And these lines by Anna Akhmatova, from one of her “Northern Elegies”:

As I were a river,

hard years altered my course.

I am not the same: over a different bed,

leaving others behind, my life has flowed.

I no longer recognize my own banks.

But who knows her own banks? Led by the hand of Thoreau and his morning – “when I am awake and there is a dawn in me” –, I watch over my infinite palimpsest on the glittering screen of my eyelids and go forth into the world with Góngora in my knapsack: “amid thorns stepping of a twilight”.

Ilha de Santa Catarina, July 30, 2016.

Notes for On the glittering screen of the eyelids.

Changing poetic topographies on Campos Gerais do Paraná

(with a journey to Campos de Santa Catarina).

Brazil, 2015/2016.

by Josely Vianna Baptista

For those who go to meet the sun

It is always just before dawn.

Helena Kolody

click on picture

to enlarge

Illustration 1

Paraná Basin Area, in South America.

Illustration 2

Schema of the geological structure of the Paraná relief. Campos Gerais is in the part between the Devonian Escarpment (DE) and Serra Geral (SG).

Illustration 3

Schematic geological section A-B passing through Lagoa Dourada and Vila Velha. V: Vila Velha; L: Lagoa Dourada; D: Devonian Escarpment; P: “Crown” of the Ponta Grossa Arch.

[Source: © Melo, M.S. Lagoa Dourada, PR – Furna assoreada do Parque Estadual de Vila Velha. In: Schobbenhaus, C.; Campos, D. A.; Queiroz, E.T.; Winge, M.; Berbert-Born, M.L.C. (edits.) Sítios Geológicos e Paleontológicos do Brasil. 1. ed. Brasília: DNPM/CPRM – Comissão Brasileira de Sítios Geológicos e Paleobiológicos (SIGEP), 2002.]

1: Proterozoic foundation; 2: Furnas formation (Devonian);

3: Ponta Grossa formation (Devonian); 4: Itararé Group (Carboniferous-Permian);

5: Dolerite dikes (Mesozoic).

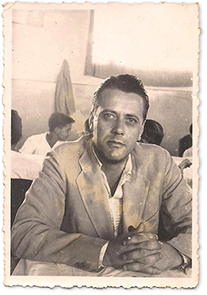

In the foreground, my mother, Vera Maria, with my sister Verinha in her lap, in a little canoe on the great, unpredictable Tibagi River, in the 1950s. Verinha is the fourth of six daughters (I am the fifth). She wrote the Brief historical and geographical glossary of Campos Gerais for this project. Behind them, on the horizon, is the island where ourfamily used to have picnics on weekends. During the same period, my father, Milton, also in northern Paraná.

Diving into the Tibagi River: to the left, me, to the right, my friend Néia.

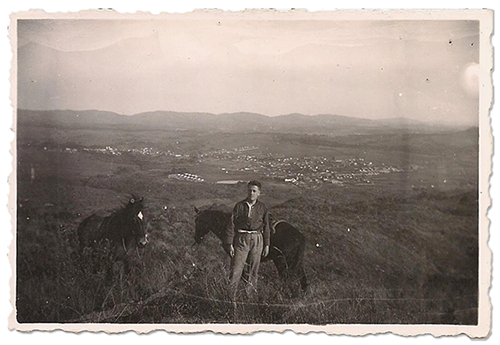

My father as a young man in Campos Gerais in the late 30's, watching over the horses of his grandmother, Anna Klüppel.