n the glittering screen of the eyelids was conceived by Josely Vianna Baptista as an excursion through a sensitive psychogeography — Campos Gerais in Paraná, her family’s native land—, a means to effect a scansion of historical, psychological, and physical time, so as to live, via the experience of landscape, an encounter irrecoverable because it never existed among generations separated by time and space. It was natural for her to invite other members of her family to participate: her son, Pedro Jerônimo (then 16 years of age) as photographer; her sister Vera Regina, a historian; Maria Augusta, her niece, an artist and architect, and her nephew, Guilherme Baptista, a geographer, the group’s generational heterogeneity deepened the symbolic meaning of the journey.

The Campos Gerais expedition was not conceived as an adventure on a merely physical plane, but as a subterfuge carried out in the interest of establishing an encounter (metaphysical) of perception of horizons, places, and sensations joined together when one lives through days which, always different, never equal, are spent on the same ground, under the same sky, in the same geographical space.

Memory’s inspiration, images that arise when one shuts one’s eyes and “sees” facts which never were, can become more palpable, more clear, when the light of those places passes through the eyelids of the dreamer dreaming those images in that same locale of sensitive experience.

What is more, that action, even if set in motion by familial ancestrality, has the power to unite all those who once lived and traveled the same soils, saw the same valleys and fields; this suprahistorical, supratemporal encounter grants kinship to all those who, whatever their reasons, walked that country. I was one of them, and those who make their pilgrimage to this place may be, in some way, the next of us to do so. Thus, it is clear that at the moment the work began to take form, it surpassed its limits, and its focus gradually widened. The different contributions of the poets and artists who were invited to take part in the work demarcated their own voices, and simultaeously linked to other dialogues (possible, or even necessary).

“The tree of the ridge”, Pedro Jerónimo’s photographic record, does not escape that exemplar. Bit by bit, he perceived that the journey through Campos Gerais opened other themes which surpassed the mere taking of pictures. For example, one of his comments gave me a new insight: “I didn’t find the campos gerais [open fields]”, he said, “it’s all become a soy plantation”. “The tree of the ridge”, a poem by Augusto dos Anjos chosen by Pedro to be epigraph and title of his portfolio of photographs, is in part linked to that perception of his. Therefore, the series of photos gives rise to a number of interesting questions. Why did that radical transformation of the landscape take place in so short a time? It is not just any transformation: it took with it a tremendous natural patrimony, and, most certainly, a cultural patrimony. What are the causes, the actors, what type of reality does this transformation reveal? New socioeconomic conflicts arise from this transformation of rural means of production, and if the gains are measurable, so are the losses. In this scenario, what does the future hold for us? Focused on the land, on the landscape, on the image of the world received by generations, it is impossible not to look for something in these questions, impossible to be free of these worries which surpass in their breadth the fundamental, gestural moment that creates art. For art approximates realities that can be separated or disconnected in ordinary perception, and can lead to that which Beckett, in Nacht und Träume, sees as the “dream of a gesture”. Moreover, as Giorgio Agamben also understood (in Notes on gesture), the task of the artist is to introduce into dream the elements of an awakening. At some point, Pedro felt that his series of images ought to be more nuanced.

And thus the journey begins. The photographs of Pedro Jerónimo (my son) taken in the Guartelá and Vila Velha State Parks are the work of an eye by nature attracted to things all around, as if it were the generic gaze of any traveler, for all who stopped at these places once were travelers, and he himself was a traveler during the expedition; a gaze which, while able to mirror the enormous fact of those panoramas, is also, because of its curiosity, attracted by the luminosity, color, or texture of any given detail. Situated on that threshold between invention and documentation, this gaze is neither the one nor the other; in any event, my son’s eye is ever-attentive to time, atmosphere and space.However, at the moment when one leaves the Park, there arise kilometers and kilometers of an unending, undefined landscape, in which not even topography seems to acquire its own expression.

In fact, extensive agricultural exploitation of the soil of Paraná has disfigured – in a vertiginous manner – the landscape through which so many previous generations moved and grew, and which I myself was able to experience in my youth. There are surveys of the alarming loss of araucarian forest cover in Paraná. F.C. Hoenhe’s Araucarilândia was written in 1930; the 2014 edition (organized by José Álvaro Carneiro) contains maps that show the disappearance of vegetal cover in the State from 1930 to 2005.¹ It’s really quite incredible. The 2005 map shows almost nothing left, and it is ten years old. At the time when I traveled in the region (the 1970s), there was still a fair amount of cover. It is usually difficult for us to calculate such an emotional and spiritual loss. We are so immersed in our own immediate problems that it is difficult for us to undertake so generous a scansion of time.

We perceive this loss much more easily in urban environments, to which we are voluntarily confined, for changes are more obviously verifiable in cities (new streets are opened, districts appear, neighborhoods vanish, and so on); in Brazil, the dizzying, unimaginable speed of transformation does not respect the fragile, almost provisional urban occupation of earlier generations. This provokes a constant alteration of our cityscapes, so much so that we do not lose “our” cities once, but several times in our lives. It is a never-ending cycle of loss: the city of our childhood disappears, and then that of adolescence, and then that of the years of university study, of our first encounters, our first loves. This rhythm does not slacken. The situation is less common in the great European metropolises. Despite the terrible destruction of war, they have transformed while yet preserving features of earlier cityscapes, perhaps in a rhythm more in accord with generational time, so that people are able to maintain the affective links which bind them to the places they grew up in.

On the other hand, there is a mitigating psychological component to the loss of urban spaces: its “constructive” character. For if we lose one “constructed” space, we gain others. This “constructive” utopia, which generations of Brazilians easily recognize and which is responsible for a good part of the characteristically urban sensibility of our modernist mentality, is almost imperceptibly self-indulgent in the Dionysian impulse which reveals a certain euphoria characteristic of our ethos, and by which we are recognized in the foreign gaze; but this impulse is second-hand: it is not the motor, but the consequence of change. Broadly speaking, our constructive ideology derives from speculation (real estate): we have no long-term experience of any stability capable of becoming a recognizable component of our sensibility.

However, if another form of stability exists, we can recognize it in the presence of Nature, as Lévi-Strauss observed in the beginning of Tristes Tropiques. The magnitude of the loss which has occurred in Campos Gerais (an enormous region) is unknown not only to a great part of a population confined to urban and “touristic” places (and there is nothing “touristic” about the vastness of inland Brazil); another part, the people born and living in the geography we are speaking of, were and are the principal motor of change; their vision is not focused on the meaning and importance of that type of immaterial, or spiritual, inheritance, but on another type of inheritance whose content is more urgent and measurable.

My inability to share with Pedro a landscape which I believed was still there, stable, in reach of his perception and understanding — my inability felt like a shortcoming, and it caused in me an urgent need to help him “see”, know and “feel” something of that geography which educated my sensibility in childhood and adolescence, during the countless camping trips I made with my schoolmates in those stopovers in the environs of São Luiz do Purunã, in the foothills of the Devonian Escarpment which divides the state from north to south, when my friends and I hiked fields unmarked by trails, in places with unforgettable names like Tamanduá [Anteater], Rio das Mortes [River of the Dead], Rio dos Papagaios [River of the Parrots], at a time when families felt not even the remotest worry about the personal safety of the young people who went off to live for days isolated in the middle of “nothing”, in those immensities spotted with araucarian groves and creekside woods, where we saw, beside the araucarians, a forest skirted with vigorous shrubs and various kinds of small trees, pepper trees, cambarás, occasional cinnamon trees, and many angico-brancos and tecomas covered with Spanish moss, which gave these surroundings an almost fairy-tale atmosphere. The rivers ran swift and cold over water-smoothed expanses of stone full of natural pools and little waterfalls in which one could stay for a good while, reinvigorating body, mind, and sensibility under the intense, yet gentle, impact of cold, crystal-clear waters.

In a formative moment, to see those landscapes again became an existential adventure: my son had to know landscapes like the ones I’d now lost, to witness the feeling of being in that world, for a day, perhaps to be able to speak of those places with his children and grandchildren. Josely realized immediately that the whole project had just curiously folded in on itself. By the addition of another, variant journey (which surprised me), the project could recuperate a psychogeographical course that had been lost in the original locale, but might still exist somewhere else in our countryside as a portion of a resilient present, not a revisited past. Such developments in the project were perfectly fitting, and broadened the project’s meaning. For example, Josely soon found out that the oldest relatives of the Paraná Pine in the Araucanía region of Chile, where the Mapuche people live today, surrounded by forests of the primeval Araucaria araucana (see photo below).

Speaking with some friends, I located a few remaining pine forests and virgin countrysides. The São Joaquim National Park, situated in the first stretch of the high country, was one of these places, and perhaps the best of all. The region is a few hours away from Florianópolis by car. I spoke to Josely, and she decided to incorporate the new journey into the original project. We planned the excursion. Remembering how it felt to sit by a campfire at night, in the immensity all around, I thought we should go when the moon is full.

To revisit the pine groves was very moving. The countryside was just as I remembered, so vast that we could only cross it on horseback. We passed under thick canopies, over narrow trails covered with loose pebbles, through creeks up to our horses’ shoulders. We arrived at the gorges that mark the succession of canyons at the beginning of the high country to our southwest, on the counterforts of the Serra Geral. Those were intense days, even though we did not stay in canvas tents, as I did in my youth, but in the propitious and agreeable inn on a ranch at Bom Jardin da Serra. Ironically, while the weariness caused by long treks and hours on horseback did not allow us the mythic adventure of campfires by night, it seemed to me that the sight of the extraordinary forests of araucarians, the gorges, and the open, stone-studded fields running endlessly past the horizon – these things were a kind of recompense for my son. It is still possible to find a parallel with the famous citation from the first European chronicler who travelled the region in 1820, Auguste de Saint-Hilaire: “This countryside is surely one of the most beautiful I traveled while in the Américas: they are not so flat as to become monotonous, as our Beauce plains, yet the contours of the terrain are not so drastic that they limit the eye. One can see very far over immense pastures to discover groves dominated by the majestic and useful Araucarian, which grows here and there in the valleys and whose dark color is in lovely contrast to the pleasant green of the grasses”.²

Pedro’s photographs of Parque São Joaquim were taken at breakneck speed, for the region possesses such remarkable beauty everywhere one looks, at every moment. The gorges and abysses, like those at Laranjeiras Canyon, are as much as 1.4 km deep. The pristine countryside we sought is covered with dense araucarian forests, and is at times demarcated by long lines of low walls, some of them centuries-old remnants of the cattle-driving days. Built from stones found everywhere around the place, these walls still protect a perfectly acclimated animal husbandry which has never been extensive. We saw goats, sheep, a few heads of cattle grazing. Our nighttime campfire could wait for another time, for surely there will be other times — but this was a moment of reconciliation between myself and the meaning of a landscape that I recovered just in time to see it again, this time with my son, and, in the midst of the vastness that surrounded us, to tell him about the world I grew up in, the world that always offers new angles of a meaning that never stops expanding.

Postscript: the journey to Campos Gerais National Park and environs

A year and a half after the start of this photograhic work, Pedro returned to the Paranaense region of Campos Gerais as one of the collaborators on the project, looking for landscapes typical of the countryside which might still be preserved. On the first trip, the team had seen only the extraordinary landscapes of the Guartelá Park canyon and the Vila Velha Park area. Now they traveled in another part of the Second Plateau; the Campos Gerais National Park is there. The Park was created recently (appropriation of the area has yet to conclude). It covers an area which still preserves some places with features characteristic of the countryside, but the extensive farming surrounding the area held by the Unidade de Conservação has already invaded some parts of the Park. The farming follows the anthropic transformation of this great ecosystem, to such a degree that it produced the great modification of the last 30 years: the contradictions inherent to the invasive development of extensive agriculture, characteristic of the capitalist means of production in the countryside, are still operating. In the area, there is in effect no management plan to promote de facto conservation. Yet, in places where the countryside is preserved, it is possible to appreciate its wild beauty, which Pedro recorded with a palette ranging from the burnt yellows to the rusty reds which suddenly flower between the stones, and the occasional presence of typical winter fog.

Another evidence of radical environmental change is the fact that there are almost no remaining communities which can be truly called rural. There is one remote area which remains an exception, and in that area there is a village called Biscaia, which was founded by some of Josely’s Basque ancestors, who came to Brazil around 1700, and populated the Itaiacoca and Cantaduvas de Fora regions.

Now Pedro has opened the focus of his lenses: he documents the transformation of the landscape; the reduction of remaining groves to make room for pasture or tillable soil and the distinctively one-dimensional character of plowed and planted ground; a world going by, unending, seen from the window of a car speeding along the roads. Diverse beauty is now confined to the clouds, to the sky, that still uncolonized part of nature. I am reminded of these lines from the poem “Clouds” by Wislawa Szymborska: "Unburdened by memory of any kind / they float easily over the facts".³ The terminal disfigurement of Campos Gerais proceeds in full force, despite the actions of environmentalists, who are seldom, if ever heeded on the plateau. The Irati region contains the few remaining araucarian forests, in two projects run by conservation units: the “Araucarian Biological Reserve” in the Imbituva, Ipiranga, and Teixeira Soares municipalities near Ponta Grossa; and the “Irati National Forest”, which covers parts of the Fernandes Pinheiro e Teixeira Soares municipalities. The area is mostly covered by native forests dominated by araucarians, or Mixed Ombrophilous Forests. The area is still the only place under a management plan (dating from 2013); the park was once held in preservation by Instituto Nacional do Pinho, which is now defunct.

Except for a few groves here and there in the countryside, the araucarian has mostly disappeared from the Second Plateau (see the map, “The high fields of southern Brazil”); these groves very often are not easily seen, as they are hidden behind the exclusivity of some private property or another.The new configuration of rural properties also affects the Tamanduá region, near São Luiz do Purunã, at the edges of the aforementioned Devonian Escarpment, which Pedro was able to visit during the last expedition. The historic Capela da Nossa Senhora da Conceição do Tamanduá, is still there. Its construction began in the beginning of the 18th century, and the lovely little chapel itself dates from 1730. However, the free passage through the open fields, which 40 years ago allowed us to follow kilometers-long trails through the preserved fields, over pristine rivers, and past caves – this free passage has disappeared. Surrounding properties block all access. Pedro’s photographic collection,The tree of the ridge, bears witness to the moment of the eclipse of some of the most remarkable landscapes in Brazil’s high country.

1 F. C. HOEHNE. Araucarilândia. Edited and introcuced by José Álvaro Carneiro. Curitiba: J. A. S. Carneiro, 2014; Facsimile of 1930 edition, pp. 36-37.

2 F. C. HOEHNE. Op. cit. p. 8.

3 From “Clouds”, a poem by Wislawa Szymborska, in a translation by Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh.

Francisco Faria (Curitiba, 1956), is a visual artist. As a draughtsman, his work is dominated by pieces made with graphite on paper. He also creates installations and works on projects combining the visual arts and poetry with the collaboration of contemporary poets. His frequently very large drawings relate to graphical and pictorial strategies of the landscape genre, with a strong focus on Brazilian landscape. Considered one of the most important contemporary Brazilian draughtsmen, his work has had numerous individual exhibitions in Brazil and elsewhere since 1982. He has also participated in International Biennials and other important institutional exhibitions. Dozens of Faria’s drawings were shown at the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, in Japan (2008), Koichi Kawasaki and Tadashi Kobayashi, curators. In 2011 he received a grant from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation in New York. He is represented by the Bolsa de Arte gallery in Porto Alegre. https://franciscofaria.com

Cave with rupestrian inscriptions, Guartelá State Park, Paraná.

Devonian Escarpment, in Guartelá State Park, Paraná.

Pedro Jerônimo and his cousin, the archaeologist Thomas Gaissler, in a sinkhole in Campos Gerais do Paraná, in July 2016. That environment is still completely preserved. Above, about 45 years earlier, Francisco in one of the sinkholes in Tamanduá, also on the Devonian Escarpment.

Josely, Pedro Jerônimo and Francisco in São Joaquim National Park, Santa Catarina.

Pine grove in São Joaquim National Park.

Cerro Nahuel (photo by Mono Andes). Araucaria araucana, the oldest relative of our Araucaria angustifolia, at the highest point of Nahuelbuta Cordillera, Chile.

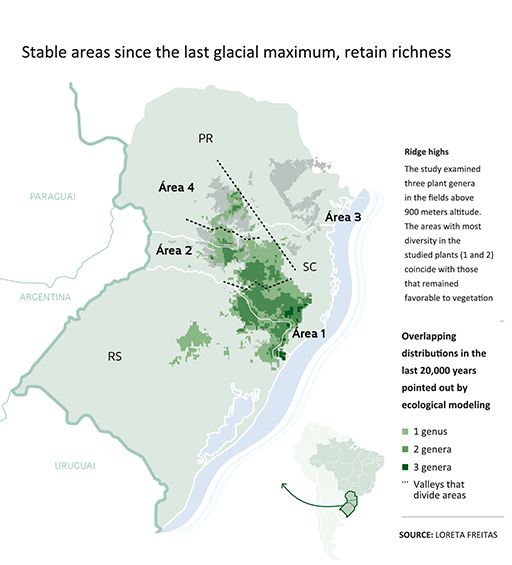

The high fields of southern Brazil

Where they were and are

The map shows four areas where the study of a group of Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) and the Federal University of Goiás (UFG), led by geneticist Loreta Freitas, also from UFRGS, "sought to understand the evolutionary history of species in the region and locate priority areas for conservation. " The researchers divided the Serra Geral in these four regions, "always from 900m above sea level, where the typical forest of the rainforest gives way to fields and forests with Araucaria." They also noted that "biodiversity is lower in the west and north directions as altitude and humidity from the sea decrease." Area 3, where most of the project On the glittering screen of the eyelids was developed, shows how the region is devoid of significant Paraná pine forest sets. Even existing reserves near the Irati region are already located in the area 4. On the other hand, the area 1, located in Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, where the team wandered through large expanses of highlands, confirms the observation that it is one of the richest in biodiversity and araucaria forests (Source: Gilberto Stam, “A riqueza dos campos de altitude”, issue 239 of Pesquisa FAPESP, January 2016).